site unseen

HOUSES IN LEYTONSTONE 1994

I had for some time had the idea of making a series of wall interventions. I had a problem finding any spaces. In Leytonstone on the route of a new M11 link road were houses and streets that were going to be demolished. The plan development attracted protesters against the demolition, in some of the houses were many artists that had been placed there by ACME a housing association dedicated to finding live work studios.

I tried to get permission to make use of these houses before they destroyed, I was denied permission. It seemed to me to be to good an opportunity to let go so I gained access without permission and began to make a series of wall cut drawings at speed. The works were only one to the public for one day

A text by Mel Gooding

(remembering)

sites of hiding seeking finding keeping in mind what was before/ bombsites gave sight of what only private eyes in love and labour had seen: the everlasting wallpapers of childhood as forever fixed with their roses and flourishes in the world as the hidden orchard behind a hedge with its perennial green apples stolen and sour every passing late summer/ as the unchanging streets on the way to school/ as the smell of creosote on wooden fences that splintered the knuckles that discovered the percussion hidden in their overlapping repetition (just as the saw disclosed the latticed rhyme of laths hidden in the plank plied by the builder at his trade in Peckham High Road)/ unchanging as the unweeded blitzed spaces invaded by rosebay willowherb and inhabited close by St Pauls and further east by black redstarts fooled by wildness/ ‘locations come into existence’ by virtue of the houses whose secret walls and stairways were exposed to weathers and eyes no longer private/ those inside out spaces cleared by firestorm for new beginnings, new occupations by flower and bird, playing child, lovers/for mew builders freeing the space `for settlement and lodging’/bringing the presencing of dwelling in which childhood ends and nothing lasts forever/being human on the earth as mortal

1

after

innumerable secrecies and numberless intimacies and layered acts of love and hate and hidden complexities of daytime and night time and miseries and felicities and familiarities and kindness and unkindness and domesticities and things done and undone and things undone and sleepings and wakenings and thoughts and deliberations and reveries and dreams and inadvertencies and careful observances and careless derelictions unseen indoors within walls in home and house

these layers revealed (clandestine disclosures) elegant simplicities !

2

clatter of bright plates

clap of pigeon wings

soft step on the stairs

rustle of treading pigeons on the roof tree

‘…those dying generations…”

3

familiar they felt barefoot the way to bed

roofed, holding safe hands

stranger, latecomer, trespasser at a private view

I stare at a carpet of birdshit, feathers and broken shells

tread warily upwards without hand hold and down

fearful of falling

4

(derelict)

quotidian in a house hold life: door hearth window skylight; the framings of a known made world: within, of hall and staircase in electric light, living room and bed room, the fire set or lit; outside, of the walled yard, grass, flowers, leaved tree or winter tracery, weather, the changing sky

images of the days’ and seasons’ turns

measures of a mortal dwelling here

openings merely now/apertures for the unseen light/entrances for wildlife to a cave a hole a darkness: shelter to lives merely given merely taken in a furious and fearful now

1 ( a working visit)

in cold half darkness he hears scufflings scatterings pigeon squab gurglings/he does not live here nobody lives here/he enters these vacancies to make them briefly ‘ locations’ once more/visits an imagined memory upon the place/dwells for a moment in the past/starts to make the works in this present/inhabits the space momentarily (his trespass revives its privacies)

2 (dialectics)

: a simple technique (a kind of thinking) that lets “something appear, within what is present, as this or that, in this way or that way’/in this way by subtraction from what is no longer present/art in this house is ‘a sum of destructions’, a negation of negations:revelation! (something disclosed/something thought)

nothing lasts nobody lives here nothing is lost

3

this dereliction is an emptying makes possible thoughts and memories

of beginnings and informings

of other orders, other paradigms,

of geometrics and architectonics,

of rhythms and intervals,

of the music in the beautiful near-repetitions of nature

of conjugations and generations

separations and endings

of other rooms in other places

of other windows, other doors

of other uses for the signs these walls

of other dwellings within such walls

4

Nothing is lost: the rubble belongs where it falls

Part of the thinking

Part of the memory

Part of the work

Part of the story

Part of the earth

M11a_14

Can you just say your name and spell it for me?

Terry Smith.

And what year was you born?

1956. Morning.

When did you go to the Leytonstone, Leyton area? What drew you there?

All my friends were living there, there’s you know because of the ACME housing situation so probably all my friends at one point were living somewhere in Leytonstone – Filibrook Road, Grove Green Road, you know the whole area really.

And where was you living at the time yourself?

I was living in another ACME house in Bow. So um but I would hang out in Leytonstone because of my friends were there, so parties, lunches, dinners, drinking, dancing, falling over, all those things happened you know in one of those roads or other.

You’re saying you was often up and down there anyway to go and see your friends and drink in the Northcote and things like that-

Yeah, that was the reason for going there.

The piece of work that you did in the houses – Sight Unseen – How did that come about?

That didn’t come about until the end, when ACME had to get the artists to vacate the houses. You know put an end to the social life, put an end to everything really in terms of that orbit of friends in that particular place together. And I tried to get permission from ACME to make installations, or kind of wall drawings in the houses that were empty because they were gonna be demolished and pulled down. But because of the crusties and they er you know the protest, they were very reluctant to do that. There was a very big procedure when the artists gave over their key they’d be met by security, the security would take the key off them, there’d be sometimes the police would be there as well. Then the builder would turn up, brick up the doors and windows, and then someone would sit there until the cement went off and then that would be the house filled up. So ACME just thought it would be just too much to have someone there knocking you know six bells out of the walls and things so they said I they denied me permission. But I thought that it was such a good idea to do this, such a great opportunity, I had this idea in my head, this conceptual idea of making these works and I just thought well I’m not gonna take no for an answer so I broke into the houses and made the work anyway.

So I just want to go back to your familiarity with the area to begin with. So who were the people that you knew living in the area?

Well, Martin Mitchell, Kitty his wife, partner, Cornelia Parker, Gary Stevens, Minna Thorton, Georgina Carless. I mean, you name names now I probably would say yeah, I remember them. I mean just loads and loads and loads of people.

So what was living in Bow like, were a lot of the people living around you people you went to art school with and so forth?

Er only Gary and Minna, I mean the rest I just know from, probably met them there actually some of them.

So was it Gary Stevens and Minna Thornton you initially visited?

Gary and Georgina. Also Mark Thomas, Anita, Steve Nelson um it’s just loads of people I mean really, really.

Cos you also did that show didn’t you with Steve Nelson in France? I don’t know if you remember that show, they had a French photographer who came to Leyton to photograph the area and it was all about artists in east London.

Oh yeah, yeah, yeah, called ‘Mind the Gap’.

That’s it.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Was that before or after ‘Sight Unseen’?

Oh before.

Ok.

I’ve probably got the book here actually.

So could you say a bit more just about the people that you used to visit in the Leyton Leytonstone area, like what their work was or anyone that kind of really stands out in your mind?

They all do, really, because you know Connie was making work and struggling, everyone’s struggling making work and trying to get kind of you know making a breakthrough and it was just a very good social time, creative time I think. You know there was no—but I mean everyone was just doing, we weren’t really making art we were just making life you know. So we weren’t really thinking about being artists in a funny kind of way.

That’s really interesting. I think that’s really sort of symptomatic of the time actually.

Well I can’t remember what we did but we all made work on the side but we just did other jobs and either people taught and you know I was doing van driving or general building work and we were all just getting by and helping each other without even thinking about what it mean you know. But the art was there, people were having shows and people were interested and I think Grayson Perry did live there?

Yeah.

I mean there’s all kind of people doing stuff and different parts of the place and you hear about people and you know but it was just a very good you know the fact that everyone was together made a big difference cos obviously you know with the Northcote pub and everyone would go there so it’s almost like, well it was a community and it’s often you get that in London you know. So I think it’s quite unique at that time and that place.

Cos you knew there were a number of places where ACME had these live/work spaces right across east London and up in Archway and whatever, do you think that’s all kind of finished now?

Well it was probably because of the housing, I mean where I lived in Bow, I mean our street, which was a derelict street for most of the time for at least half of the time I was there so only artists and squatters lived there, you know. Next door were painters, film-makers, musicians. Bruce Row opposite we had positions there and at the end of our street we had the De Gway organisation – remember them? De Gway?

No I don’t.

They were called the De Gway organisation and they just a group of guys I don’t know what they did but they--people would knock on the door and say “Got any black paint I can borrow?” you know so you had that kind of thing where it wasn’t just sugar and milk it was you know materials and stuff. And cos it was an empty street you know I remember there being certain times we’d just drag the piano in the middle of the street and start banging it about you know kind of but then you know the area got gentrified so suddenly you know now it’s all lots of little kind of flower pots and stuff but at one point no one would come down our street because they were terrified of you know there’s dogs and the squatters and the artists. And I’m sure like in, where was it? Spamby Road and those places further west you know the same thing, the same communities there, kind of you know Kerry Trengrove and Alice and all those people so there were these pockets because ACME had houses to give people rather than studios. And I think houses by their nature are more social where I did have a studio, and ACME studio, for a while in Orsbury Road and it was very unsocial you know just because people you know have precious time and they kind of when they get to their studios they want to work, they don’t wanna party, a coffee or whatever, so you understand that but it does you know and I think it’s a shame but studio blocks don’t have that same thing. I think it’s rare that you know I don’t know now whether there are pockets of artists living in the same place.

So when you went up to Leyton/Leytonstone, what streets did you frequent, where people lived?

Some I can’t remember—Grove Green Road, Filibrook Road and there’s a few other roads back from Grove Green Road, whatever they were called.

Dyers Hall?

Dyers Hall Road oh yeah. Georgina lived there and Steve I think. There’s another one further down I think.

Colville Road?

What was it called?

Colville Road.

Maybe, I mean. But I mean it was just packed full of people.

Can you describe, like you got to the bit where you were about to break into these houses. Can you remember which was the first house that you went to, I mean even the street name and describe from there what you did to the house and what the house was like when you entered?

Well they were empty. I mean the thing was I said to everybody I broke in but I didn’t really break in because actually all the artists who gave me their houses did it as a favour but we had to kind of go via, we couldn’t admit this to ACME, so if anyone found out I’d have to claim that I broke in but I just think well I was kind of given the key by the artist just before they left and I would do the stuff and then give it back so it was a way of um illegally being the kind of with consent in a way, at least consent from the artist not the—and most of the houses you know houses I’d actually sat in, and drank in and slept in at various times so they were quite kind of er close to me you know I knew the rooms. And I just liked, I mean this was an idea to make these wall works and I had no idea whether it’d work or not so for me the great thing was I could just do this stuff in private, no one would see it. If it didn’t work then it was fine and I’d get a chance to explore and experiment and I think at the very end I did get some people to come and see it but most of the time through I didn’t. And I photographed just for my own kind of snapshots really and I’m really grateful to myself for doing that because now it’s become the archive but I wasn’t that interested in photographing it and I’m still not that interested in archiving anything. I ought to be cos they’re ephemeral most of my work.

I remember quite often at the time, and it might seem strange to some artists now, then artists would make work and often not document it and then later the work gets destroyed or left somewhere or whatever. And so I don’t think there was this kind of I suppose drive all the time to document artwork the same way, it just seems things have changed.

Well to one degree we were kind of like that yeah, but also we had no idea what would come next you know we didn’t think what would be next, we just thought this is now and we’d do stuff and you know like anything you just deal with what you have to deal with you know, I mean nobody thought anything about that I don’t think.

Could you describe the interior of the houses because I mean for example, I’d heard about the Fillebrook Road houses and that they were quite big but I don’t know any more about them than that. What were those houses were like?

Well yeah I’m not sure what period they were. They weren’t Victorian were they? They must be Edwardian I guess or something. But they were big I mean compared to Grove Green Road, which had more normal size houses, they were much just bigger really. But I mean they were very ordinary houses, I mean fireplaces, skirting boards but the kind of house you might see in Islington actually, that kind of extra foot here or there you know and they were big rooms and I mean they were very generous spaces to live in I think.

Were the hallways quite grand?

Mmm. I don’t know I remember particularly. But you had to go up to walk up to them so they must have had a. I don’t remember them having basements but they must have had something because you did walk up to them I think. But they used to have big, big, back gardens, huge back gardens. I can’t remember a back garden being anything other than this huge forest. You didn’t kind of cut your way through you know I don’t think anyone ever did anything with their garden.

So can you describe the pieces that you did?

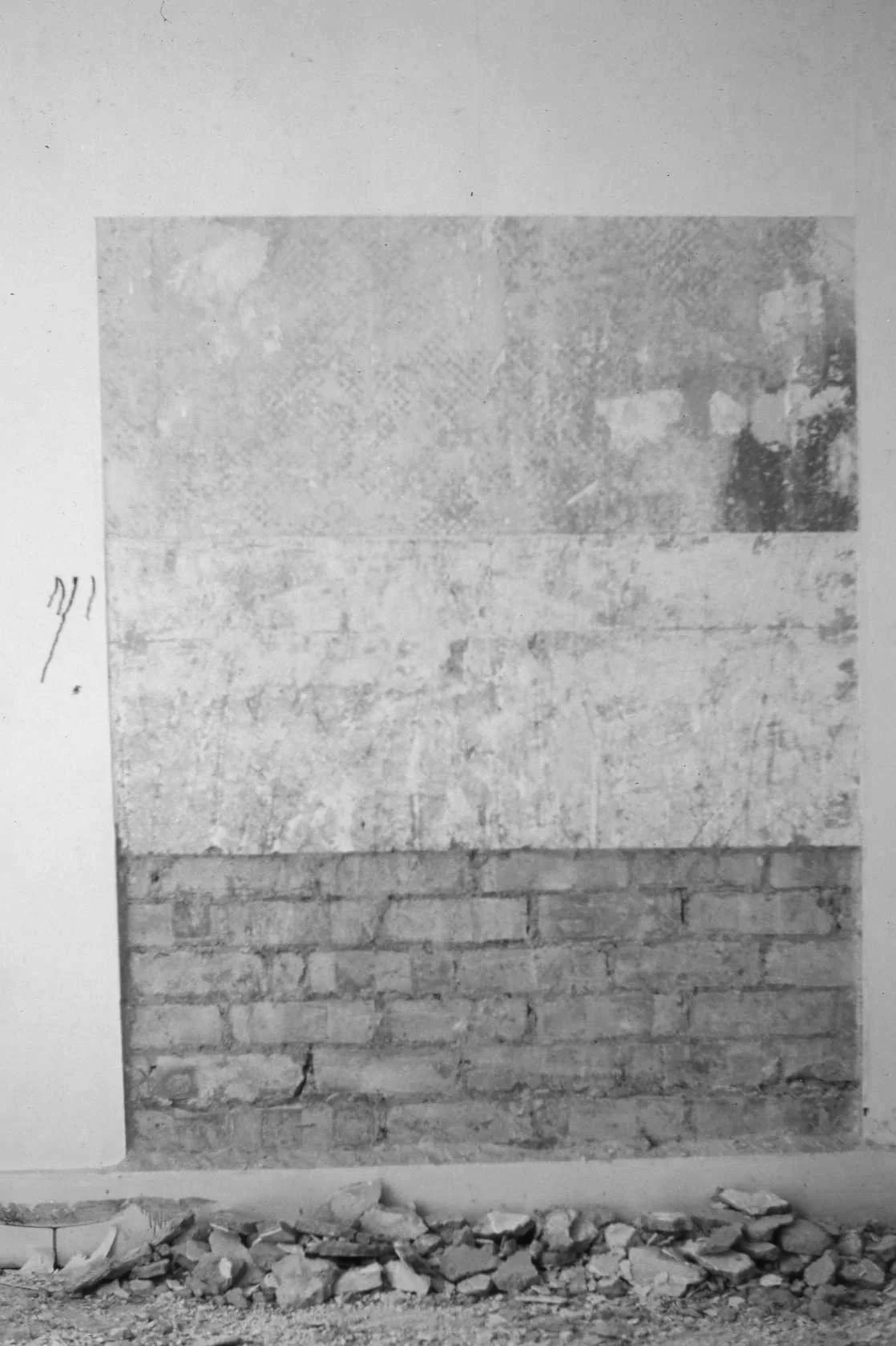

Well er I went in there without a plan really, I just thought I’m just gonna see what happens so I just you know on one piece--one thing I discover was, which I’d discovered previously and why I had the idea to do it, was that plaster was put on different levels, so there’d be a kind of base level, a kind of second level and then there was finishing level. And then you get the bare brick beneath it. So I was just cutting back into that so I just kind of quite precisely chipped away so that on some pieces, one piece called ‘Layers’, where I just simply cut back three or four layers and just exposed I mean really I was just exposing what was there. And it’s something which I’m still doing now in you know paper works that I work and everything is just about cutting through and getting into the interior of it in a way and back to the sort of whatever the surface might be, what’s beneath that surface. And I’d take things like buckets, anything that was like a shape that I might like or so I took kind of referencing bits and pieces that I found in the space um and the whole point for me was that no one would see the work so I could do whatever I like, I could fuck up and foul and nobody would know, I could experiment and try new things out er and I could find out what the material does, you know the harder the material the easier it is to carve it, the softer the plaster it’s more difficult, falls off and kind of. So I just enjoyed getting there with a drawing pad and just making up things as I went along. Sometimes I didn’t draw until afterwards and I’d just see what you know if too much falls off I’d change my plan. What’s important for me was that it set in motion a kind of process that I’m still working on right which is kind of you know I still experiment, every single show I do is an experiment you know I always push things a bit further than my, you know what we call it now is the comfort zone but you know I just extend the area that you know and go a bit further.

Cos there’s one piece which I think is in the Fillebrook Road. I got a postcard through my door of that image from Camden Arts Centre years ago. I think it was from Camden Arts Centre.

No, the Adam Gallery I think.

The Adam Gallery. And when I first saw the image I thought it was the outline of a fireplace cut into the plaster but then later I thought it looked like the top of a classical plinth. So where did you get that imagery from?

A bit of both, I mean I think that the area that I took it from was an area where there was a radiator that had been taken out for kind of recycling or whatever and so I think the skirting board wasn’t painted the same colour so it kind of so I wanted to do I was interested in columns which later on I took on in another way, in another place. But at the time it was that thing of being a fireplace on top of a column, it was just that ambiguous.

Was that work developed, at the British Museum?

Hmmm.

Could you say something about that piece of work because that was a little bit of sort of hit and run like the Leytonstone sight Unseen?

Well a friend of mine worked there, a designer, and he knew my work and in fact he saw the work at the Adam Gallery, which was the first time I showed the work from, there was a direct connection between that work I made in Leytonstone, which was ’95 ’94 – ’95 was the first time I had a solo show at the Adam Gallery and from that lots of things came out of that and one thing was the British Museum. He saw the work, said there’s gonna be a big room, it’s gonna be refurbished in the British Museum room 49 and if I wanted to come along and do an installation there you know. So we thought but we had to do it within I think five weeks and we realised or he realised that it would be impossible to get permission to do it. So the best thing we could do was just simply just do it because like all these institutions, if you’ve got confidence to walk somewhere and ask somebody for a key and you’re wearing workmen’s clothes and stuff you get through. So we began the whole process of making this project and you know when I get a huge space to work in and I just put a request saying I needed a scaffolding tower and it would arrive the next day so it was fantastic. And nothing was written down so nobody could trace it, there was no paper trail. And eventually when they did find out they tried to stop it but they realised it’d gone too far cos it’s been in the press and on the radio so they decided the best way to stop it was to simply ignore it.

Oh. And what did you actually do in that room?

Well there was a huge the wall was a huge wall and the piece I made was 35 feet long by 17 feet high and the thing about the British Museum that caught my attention first of all was that it’s you know it’s just columns at the front of it, it’s just columns. You take away the columns and there’s no design to it really. The architect of that was a guy called Smirk.

Yeah.

I thought it was a great name for an architect, a great name for anybody. So the column was most important, and I knew from history that Karl Marx wrote Des Capital in the reading room and I thought well the British Museum is really a great place to have written that piece of work because it is about capitals, about what you do when you have too much and how you spend it. So I called the piece ‘Capital’ and I found out that the top of a column is called a capital so it just made sense to make this very, very enormous column you know and carve it in so I got some photographs and drawings of capitals and I just simply drew them every single day. I just drew ‘em and drew ‘em and drew ‘em and drew ‘em, kept drawing until eventually I scaled it up and scaled it up, so the last one I did was nine feet long and then I thought now I can draw it so I, because I didn’t want to square the wall the up and leave marks on the wall so what I did was imagined the large nine foot drawing on the wall and then marked where I thought things should go, like the spiral, the top and then did it that way.

So were you drawing with a pencil or were you carving?

First of all just drawing with a pencil, just two weeks of drawing and then well lots of bits of drawing on paper but I needed to get familiar with the image to the point where I could do it without even thinking, you know I could just do it without even looking at one.

And then you drew that onto the wall eventually?

Drew it onto the wall, and then started to cut into the wall.

Oh ok. So you know that because you wasn’t really officially allowed in the space did you find out what happened when you went? Because were they renovating that room?

Well yeah they planned to strip all the plaster off so I wasn’t in fact you know I wasn’t it wasn’t a vandal that you know they already decided to do that, which is why I was doing what I did. So eventually it got completely stripped off.

And going back again, cos you mentioned the Adam Gallery in 1995, where you did your first solo show. Was that documentation of ‘Sight Unseen’?

No that was a completely different show, I mean it was the same thing you know cutting into the walls and Adam Reynolds who ran the gallery was you know not only gave my first chance really but was incredibly supportive I mean you know galleries and museums since then have always been slightly worried when I’m gonna cut into the wall but Adam just was quite happy about it and said, “Well we know a plasterer, we can fix it quite easily, it’s no problem.” So his faith and you know he was influential I think in lots of artists’ work um and um no and also I had my first review there cos I sent slides of the work I did in Leytonstone to Sarah Kent and told her that the show was coming up at Adam Gallery so she came and saw the work in progress and I was doing it and she wrote a review of it and a really nice review and it was the first time I got a review.

Yeah and um I suppose what I want to know is just a little bit more detail about the houses, cos you mentioned the Fillebrook Road house and then you said that you went into three houses – what streets were they on?

I think two were on Grove Green Road and one on Fille—I think.

There was definitely one in Fillebrook Road because the interior of the space is so big. So how long did you work in those houses for?

I just had a few days you know between the handover of the key so really I just really had a day, two days.

That’s amazing cos it looks like a really big piece of work.

I work fast (laughs). I was only caught once there by security, that’s the other thing I had to—

Tell us about that.

Oh they just kind of came in, they just suddenly heard me banging away there and kind of came rushing in cos I was standing there with my tool belt on, huge hammer and chisel, covered in dust and they just looked at me just you know even though I must have been half the size of them they’re just terrified and ran out again. And that’s also why I was working fast because I didn’t know when I’d be stopped, you know.

Yeah. So that was the only close shave?

Yeah.

Cos during the other times did you just lock up the house and go away and give the keys back to the artists and they dropped them into ACME?

Yep.

So even, that was 1994 so you know from what you were describing it was such a big deal when people left the houses and someone came to brick them up, did the artists have to wait by the house or did they just drop the keys into the office?

I remember there being a very, like a relay you know the key would be handed over, someone would take the key you know because they were terrified of the crusties getting in and squatting.

Yeah.

So they had a very strict procedure to make sure that didn’t happen.

So you mentioned that one of the houses was in Grove Green Road. Did you ever go down Claremont Road and see what that street looked like at that time in 1994?

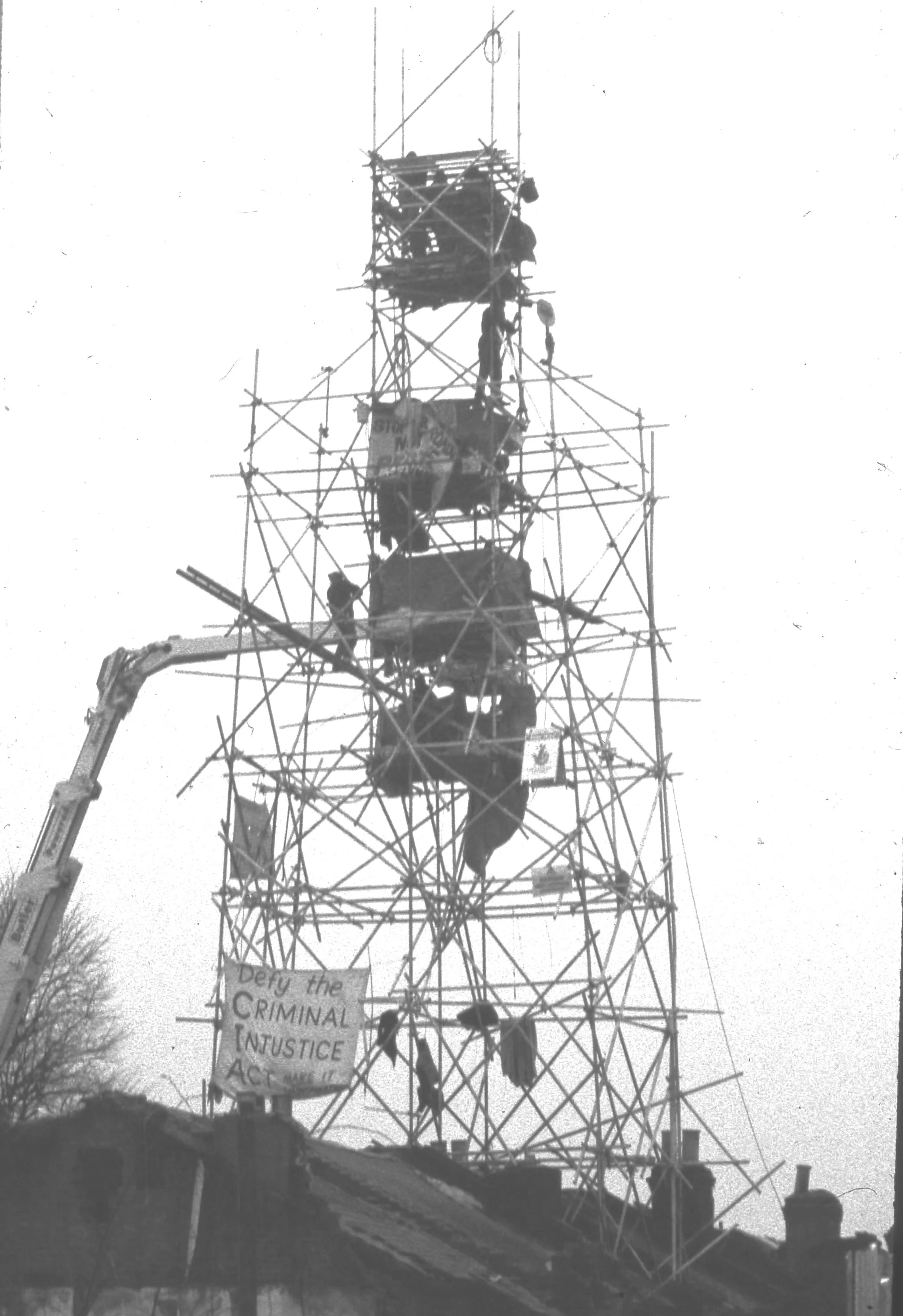

Mhmm. You mean with the big scaffolding tower?

Yeah, can you describe?

I’ve got pictures of that too.

Really?

It was a wonderful piece of sculpture really, or not sculpture but it was a wonderful installation. It’s just climbing, gigantic scaffolding tower going up there. I remember I mean you know all that time there were lots of press around, lots of TV people around, lots of protesters and stuff, but the whole area was I mean the whole link road was kind of a huge you know debate about that, nationally.

And because you’d been going down to the area and seeing your friends over the years, I mean what kind of period are we talking about when you were going in and out of the area?

I can’t remember I mean it’s just anything before ’94, ’90, the five years, six years period before then.

Yeah, so over that period you would have seen—

Probably ’88, 1988, ’89.

So you would have seen quite a lot of change to the streets.

Since then, yeah.

I wanna get a sense of like what it looked like towards the end really.

Well I don’t really remember it being much I mean it just you just lost roads and roads and roads, suddenly you’d lose a whole road you know I mean it just became you know and everyone began to move out bit by bit, it just stopped being a centre of everyone’s life and just faded out really, cos the protester took over the sort of area in a way.

When you were in Fillebrook Road was the street half knocked down or part of it - or hadn’t it got to that stage yet? Can you remember?

I think it was yeah there were bits of it knocked down I remember there were bits of it knocked down. I’ve got photographs of it actually, of parts being knocked down. I mean they would knock it down as soon as they could, you know um so yes I remember that. But lots of corrugated iron, lots of odd houses staying still there you know while people are protesting and fighting you know.

Oh, so you’d get maybe a row knocked down and a house standing and another bit.

Yeah, yeah yeah.

Oh. Can you remember that?

Yeah it just be people would paint interiors, they’d paint pictures over the inside of it, outside of it, it just got kind of you know just like any you know when the squatters are in somewhere and they kind of and they’re hanging on, holding on. You know I think they tried their hardest not to get too rough because they didn’t want the press coverage you know so the authorities were kind of smart about how they, or creepy about how they did all that but I mean people held out.

So you’re talking about Claremont Road and the last house at Fillebrook Road?

You know I can’t remember the that clearly.

Where?

All over the place really, I mean there was bits of houses here and bits of houses there pulled down.

So the series of installation pieces you did in the houses in Grove Green Road and Fillebrook Road, some of them are quite formal like rectangular quite minimal in a way, and then you’ve got the ones which, like the one that looks like a fireplace and the top of a classical plinth, and they’re all sort of very much in that formal vein, and then you get to ‘Sore’, and the other one called ‘Stretched Flag’. How did that happen?

Well I think that one thing I’ve, I guess if I think about it, everything that I am now was in that work, in that you know I work in different media and I work and I work in different, even within the media I work in different ways. So maybe I might work with video in quite a sculptural way or I make kind of narrative film, you know I think that I’ve never been, never felt that I was a figurative artist or abstract artist, it never really, never a label that I ever felt I needed to attach to myself, one or the other. The one that I kind of have is about like what Richter says, you know I have no style, no continuity, no you know no sense of anything really, I just make work and there are things that you have to respond to or you want to respond to in an abstract way or concrete way and other times you kind of in a more narrative way. With the piece ‘Sore’, that was, it was actually at belly height and I remember hearing about bed sores and I was horrified that bed sores can happen that way, that you can just by simply someone being in bed for a long time can you know can destroy the tissue there and there’d be a hole inside that person where you can you know it’s. And later on I actually worked in a hospital and saw them, you know.

So in a way that pressure, like the weight of something in one place.

Actually it was before then I worked in the hospital.

Oh.

That’s right. It was before, in the late ‘70s. And saw bed sores and saw people in bed – I worked in the hospital, in a hospice for a year and a half. And seeing people with sores being dressed and it was really like a kind of huge hole, I mean it was like a you know almost the size of an egg cup. And I’d see nurses just putting in you know bandage and stuff and wadding into that kind of sore. And just the idea that that kind of wound can happen just by simply someone lying down. So in that piece ‘Sore’ I just kind of imagined, because the layer you know the different layers in the plaster that I mentioned before, just cutting through that just very gently, very thinly, almost at the same height as a belly. Almost as if someone had been leaning against it for a long, long time and just gradually wore away. I remember a quote by Quentin Crisp, I’m not sure if I remembered it then or since then, but he said that you know he tried to get through into society and you can do two things; you can keep knocking against the door or just lean against it, and if you lean against it, eventually it falls through and I think that idea of that you don’t always have to be you know pushing something, just leaning might be enough. So that’s how that piece came about really.

And I suppose that idea of waiting as well, which I’m very interested in because that’s what a lot of the protesters did actually – waiting on the roofs or corners and not actually really doing very much but making presence felt really. I mean, I don’t know because when I see that piece ‘Sore’ I think of what was happening to the whole environment, like you knew all those buildings being knocked away, the whole place being scarred and mowed down. I dunno just that little piece ‘Sore’ on that wall seems to encapsulate the whole place inside out in a subliminal way. I don’t know, maybe I’m reading too much into it.

Well you’re reading your own things, I mean I don’t think they were there for me at the time but I think that’s what is interesting about art, is that you know people can, that often you do things without really you know they develop a meaning later perhaps. The ‘Stretched Flag’ piece became—

Mmm. Cos that’s a union jack isn’t it really?

Yeah, totally. I mean one of the protesters had made a flag out of the negative colours you know. And then another person had used, I thought it was so interesting to take the flag and then by a simple switch to make something to make the flag quite a different thing, to kind of grab, to re--- And at that particular point in history you know the union jack you know was not you know it was not a union of jack it was kind of a diversity of jack. Kind of you know anyone that had you know the union jack was really about the right wing and the BNP party and the National Front. So for a long time you know the union jack was not an object you’d ever brandish without it having implications that you didn’t wanna have. So I wanted, and I’m also a big fan of Jasper Johns’ work and his work ‘Flag’ with the American flag and one night when I was doing that project I was in town and saw this stretched limousine trying to get its way round the corners of London, trying to you kind of this cumbersome, bizarre thing. And I just thought that’s interesting that it had been stretched like this and I just thought well ok I wonder if I can stretch the flag to the point where not only is it longer than it should be, but that it has no, it has the kind bare skeleton of its logo. And that’s the other thing about it, was its logo, that you know it’s the logo for the country you know it’s the trademark UK is you know the union jack, so I was interested in that as well, that aspect. I used the union jack a few times actually, I did a painting that was about the augury of the mining strike cos a lot of my work at that time was about those kind of issues so I made this big painting about the miners’ strike and used a flag for that and sort of dripped on and scarred it, and washed it off and so I’d used a flag a few times in drawings and in paintings and then this time in sculpture, wall drawing.

I do remember there were a few artists actually working with union jacks around the late ‘80s, ‘90s and I remember Keith Paper did that piece called ‘There ain’t no black in the union jack’ and I think a curator organised a show about work with union jacks but I can’t quite place it together actually at the moment. I just think maybe that was so much an image of that time (laughs).

Well it’s about identity. You know it’s about where you know what group you’re part of, you know. I think when the crusties took that you know the negative colours of the union jack and played with the colours of it and everything they kind of grabbed their identity but they used one that was meant to the authority, the establishment, and used it to represent the people that were kind of off-centre. I don’t mean off-centre; I mean you know on the edges. And I thought that was a great tactic, to kind of you know take what’s familiar and subvert it, you know, because subversion has to be that, I mean you can’t subvert subversion I mean you have to subvert what’s established.

And also I remember you mentioned Kerry Trengrove, because he did that piece at the ACME gallery where he tunnelled through the building and I suppose also with your work then, you were doing something similar using the house as material, using a building as material. I was thinking there’s also tools in your work, there’s kind of this industrial feel and just wondered where that comes from actually?

Well it comes from my background, I mean from working-class background, doing jobs you know involving you know manual jobs you know, where you had to be good at something or you get your fingers off, you know so you need to learn to use the hammers and chisels and stuff. And I think also from the very beginning, you know from growing up in the east end you didn’t really see much art. The first time I got taken to an art gallery, in fact twice I got taken when I was 15 and just 15 and a half, one was to the Commonwealth Institute, as a kind of educational trip the school made, which didn’t really interest me very much but in the foyer was these sculptures by, what I later found out to be, Anthony Cairo sculpture, this kind of long, er, you know iron frames, iron beams, kind of industrial bits that he uses, used then. I was just amazed by it, I was knocked out, this kind of you know they’d been painted orange and I knew the materials, I’d seen them in building sites and stuff but I asked my teacher what it was, he said it’s sculpture and I said, “But I thought sculpture was statues?” and up to a point I thought sculpture was statues – when you saw a statue, that was what sculpture was. And I just thought this is fantastic cos I can do this, but I didn’t mean that in a cynical way, I just thought this is a material that I understood and recognised. Well I had the same thing when I first saw Carl Undria’s work and I saw you using bricks and you know objects which I’m familiar with, there was no bronze where I came from, there was no paintings where I came from, you know I didn’t see that stuff daily but I saw bricks daily.

So when you were younger and you were looking at that artwork in that way was it like people in your family were builders or something or had you done building work by then?

I’d done building work but you know you’re just sort of familiar with it, I mean you know what brick looks like, you know what a steel girder like you know these are things you’ve seen you know and they make sense to the industry that your parents probably earned a living from in some way or another or which the area earns a living from.

So what kind of jobs did your family do, like your mum and dad?

Dad was a plumber, and then he became a heating engineer and then he became a manager of a swimming pool. Mother was a seamstress, did this kind of a seamstress. So the rag trade.

Did you do building work as a job and then go to art school or was you doing it on the side, did you go straight from school to foundation and then art school?

No, I had a gap. I left school and went straight into work, worked for Polydor Records.

Yeah.

General labelling just taking the records out of the, you know and packaging them up and sending them off to shops, that was what I did. And then er my mother insisted that I go to college in some way or other so I went to Havering College, doing window display and exhibition design, and then was thrown out after three months and then the person who through me out felt a bit guilty I think and so she got the interview in East Ham foundation course, which I thought was a building course cos it seemed to make sense, foundation you start at you know you learn how to do the foundation, you learn to do the walls and learn to do the roof.

So you didn’t even know it was art?

No.

How interesting.

So I went there and had an interview and they looked at all my drawings and just thought it’s a bit weird well I keep thinking, well I suppose you’ve got to draw things, you’ve got to draw walls and stuff of foundations and stuff. And then I could tell from the fact that as soon as I got there I knew it wasn’t quite right because they were all wearing velvet jackets and stuff and it wasn’t what I thought builders would wear. And then I found out about Duchamp and Picasso and you know everything and it was just it was like suddenly finding a whole world of amazing things, you know, and I still enjoy finding out about things.

That’s really interesting, like how it all has sort of fed in. And a way that ‘Sight Unseen’ piece you said was quite a lynch pin for you recent work. Can you explain more, how?

Because you know when I do shows now, no matter where the shows are I do two things: I treat the smallest, tiny, artist-run space as if it was the Tate gallery or Museum of Modern Art, New York and I treat big museums as if they were like the smallest, tiny, artist-run space in Leytonstone. You know I just treat them exactly the same, you know, and I tend to experiment every time I do a show, you know it’s a nightmare for the curators and everyone doing press releases cos I’ve no idea what I’m doing until I get there and I resist the idea of making a press release because I don’t know I make change my mind at the very last minute and I often do. And so it set the idea, because what happened in Leytonstone was I could do what I wanted to do, to experiment, and I just thought this is the right way to be. I thought I don’t wanna stop doing it, I don’t wanna start being good at something and then just do it cos it would be boring, and I still find doing shows really boring. I mean there’s nothing more boring than putting your work in a gallery and then you walk away. You know just as people start to arrive. So I like the idea of engagement, I like the idea of just talking to people and people see the work and changing it. And I change work all the time, I fiddle with it, even films I’ve made I keep changing them and altering I mean I’ve never really finished anything.

What art school did you go to and when did you graduate?

Thrown out of the Havering, went to second term at East Ham foundation, but I was 16 at that point so I was too young to do the main foundation, I did a preliminary foundation. Then the following year did the full foundation then you just like you’re meant to apply for like I remember I looked at Cardiff, I looked at a few places, I went there in a kind of coach for the school and I just picked on Goldsmiths cos it was simple it was the easiest one, it was the local. So I didn’t go there, I just simply applied and went there for the interview and just took because I didn’t have a portfolio so I had a suitcase, I took my suitcase packed full of drawings and notebooks, I wrote a notebook all the time. I went for interview and Richard Wentworth was on the panel, thank God, you know, and he said as soon as I arrived with a suitcase he just thought this is the kind of person we want.

So you did your… was it your BA at Goldsmiths?

Mhmm.

And did you do a post grad or did you?

Eventually, yeah. I went to, I applied to Chelsea didn’t get in after about a five year gap or something. I ended up going to Birmingham, doing an MA in Birmingham, which was good and bad.

And then was it after Birmingham that you came back to the east end?

Yeah.

So when did move into your place in east London?

Must have been ’86.

Ok. And I think you said that ‘Sight Unseen’ was the first piece that you did in an site specific space, and that you weren’t really showing.

Oh I’d show anywhere. I mean I couldn’t get a show if I’d paid loads of money for it, I mean I just couldn’t get my work anywhere really. Er, you know I applied to Whitechapel Open, every year, you know, every year I got rejected, which I kind of minded and didn’t mind you know I just felt it was my local gallery, my local space, I’m an eastender, you know, I felt like I should apply for it cos that’s you know. And rejection’s just something you gotta live with, you know, I’ve lived with that all my life you know so it’s not too different now than it was then, really, just different kinds of rejections.

And then you eventually did get some work in a Whitechapel Open didn’t you?

Yeah, one occasion. Once I got inside that was it, I wouldn’t do it again.

What year was that?

’96.

And what did you show?

Actually I showed that particular year the open was in different spaces, so it was in the commercial space that Keith Ball organised and he’s the one that selected so I think it’s the reason why I kind of, and Richard Wentworth too was one of the selectors too so I think that’s another reason why Richard was good. The area it was shown, the commercial are, was in Spittlefields. So my mum was born in Bethnal Green and that area and worked as a seamstress there and my earliest memories of her are sewing and so I got these labels, you know those labels, those name labels you can get?

Mmmm.

I got this company to, a company called Cash that was the name of the company, to get lots of labels made with my name on it, different colours, so on the wall of the gallery I just simply put a big metre square with pins, dress-making pins, these name tags of my name because the things about the Open was everyone was trying to make a name for themselves so I thought I’d make my own name for myself and put these up. And I sold them off the wall, so people could buy them off the wall and take it away with them so I think about £3.50 or something. I thought you know if I sold the whole lot I’d make a lot of money, I’d make hundreds of pounds or something. I think I sold eight or something.

So you mentioned that really your first contact with the Leyton/Leytonstone area was that you got offered an ACME house there.

Yeah.

When was that?

Must have been 1984 or 5, 5 probably.

Can you remember what road it was in?

Erm I think it was Dyers Hall Road, I have a feeling. Roger said to me I had to look at I had to take the, I was living in Birmingham at the time and I had to take the house or not and move in within a week cos it was that kind of quick and I couldn’t do it so they said well leave it, we’ll probably, they’ll be another house coming up. So I was on the waiting list. In the end so I got offered a house in Bow, which I took. But at the time you know I was very close you know to actually being there as well.

What condition that house was in?

Err. No memory of that at all. I vaguely remember going in and looking at it but I’ve no memory really of what—

What it was like. When you applied to ACME was there like an application form and did you submit slides or how did you contact them and get on their list, can you remember?

I haven’t got a clue actually, I can’t remember. I mean I knew Roger and David and Jonathan because of the ACME gallery they had, you know, on Shelton Street in Covent Garden so I really can’t remember now how I got on the list. I think I just simply wrote to them I think or phoned them and then and you know, Mikey was there too I think.

Mikey Cuddihy?

Yeah.

When you turned down the house in Leytonstone in Dyers Hall Road, did you have to wait very long, when was your next offer?

I think it was like a month and a half, two months.

That’s really good.

Yeah.

And so when did you move into that house in Bow then?

It must have been November because I remember it being very cold. I remember it took two trips in transit van at like three o’clock in the morning, it was horrendous kind of situation to be you know moving out of one place without any money and whatever it was, we just hired a transit. And then second time, actually we also hired a man with a van from Birmingham to come down with sort of on trips. And I went to Birmingham about a year and half earlier with you know enough stuff to fill a car and came back with you know with a Luton van and two transit vans full of stuff.

The End

Project Details

Name of Interviewee: Terry Smith

Project: M11

Date: 21st August 2007

Language: English

Venue: Artists studio, Stratford/Bow

Name of Interviewer: Alison Marchant

Transcribed by: Anna Cant

Archive Ref: 2007_esch_m11a_14